Embryo drawing

Embryo drawing is the illustration of embryos in their developmental sequence. In plants and animals, an embryo develops from a zygote, the single cell that results when an egg and sperm fuse during fertilization. In animals, the zygote divides repeatedly to form a ball of cells, which then forms a set of tissue layers that migrate and fold to form an early embryo. Images of embryos provide a means of comparing embryos of different ages, and species. To this day, embryo drawings are made in undergraduate developmental biology lessons.

Comparing different embryonic stages of different animals is a tool that can be used to infer relationships between species, and thus biological evolution. This has been a source of quite some controversy, both now and in the past. Ernst Haeckel at the University of Basel pioneered in this field. By comparing different embryonic stages of different vertebrate species, he formulated the recapitulation theory. This theory states that an animal's embryonic development follows exactly the same sequence as the sequence of its evolutionary ancestors. Haeckel's work and the ensuing controversy linked the fields of developmental biology and comparative anatomy into comparative embryology. From a more modern perspective, Haeckel's drawings were the beginnings of the field of evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo).

The study of comparative embryology aims to prove or disprove that vertebrate embryos of different classes (e.g. mammals vs. fish) follow a similar developmental path due to their common ancestry. Such developing vertebrates have similar genes, which determine the basic body plan. However, further development allows for the distinguishing of distinct characteristics as adults.

Famous embryo illustrators

[edit]Ernst Haeckel (1834–1919)

[edit]

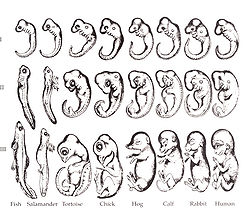

Haeckel's illustrations show vertebrate embryos at different stages of development, which exhibit embryonic resemblance as support for evolution, recapitulation as evidence of the Biogenetic Law, and phenotypic divergence as evidence of von Baer's laws. The series of twenty-four embryos from the early editions of Haeckel's Anthropogenie remain the most famous. The different species are arranged in columns, and the different stages in rows. Similarities can be seen along the first two rows; the appearance of specialized characters in each species can be seen in the columns and a diagonal interpretation leads one to Haeckel's idea of recapitulation.

Haeckel's embryo drawings are primarily intended to express his theory of embryonic development, the Biogenetic Law, which in turn assumes (but is not crucial to) the evolutionary concept of common descent. His postulation of embryonic development coincides with his understanding of evolution as a developmental process.[2] In and around 1800, embryology fused with comparative anatomy as the primary foundation of morphology.[3] Ernst Haeckel, along with Karl von Baer and Wilhelm His, are primarily influential in forming the preliminary foundations of 'phylogenetic embryology' based on principles of evolution.[4] Haeckel's 'Biogenetic Law' portrays the parallel relationship between an embryo's development and phylogenetic history. The term, 'recapitulation,' has come to embody Haeckel's Biogenetic Law, for embryonic development is a recapitulation of evolution.[5] Haeckel proposes that all classes of vertebrates pass through an evolutionarily conserved "phylotypic" stage of development, a period of reduced phenotypic diversity among higher embryos.[6] Only in later development do particular differences appear. Haeckel portrays a concrete demonstration of his Biogenetic Law through his Gastrea theory, in which he argues that the early cup-shaped gastrula stage of development is a universal feature of multi-celled animals. An ancestral form existed, known as the gastrea, which was a common ancestor to the corresponding gastrula.[7]

Haeckel argues that certain features in embryonic development are conserved and palingenetic, while others are caenogenetic. Caenogenesis represents "the blurring of ancestral resemblances in development", which are said to be the result of certain adaptations to embryonic life due to environmental changes.[8] In his drawings, Haeckel cites the notochord, pharyngeal arches and clefts, pronephros and neural tube as palingenetic features. However, the yolk sac, extra-embryonic membranes, egg membranes and endocardial tube are considered caenogenetic features.[9] The addition of terminal adult stages and the telescoping, or driving back, of such stages to descendant's embryonic stages are likewise representative of Haeckelian embryonic development. In addressing his embryo drawings to a general audience, Haeckel does not cite any sources, which gives his opponents the freedom to make assumptions regarding the originality of his work.[10]

Karl Ernst von Baer (1792–1876)

[edit]Haeckel was not the only one to create a series of drawings representing embryonic development. Karl E. von Baer and Haeckel both struggled to model one of the most complex problems facing embryologists at the time: the arrangement of general and special characters during development in different species of animals. In relation to developmental timing, von Baer's scheme of development differs from Haeckel's scheme. Von Baer's scheme of development need not be tied to developmental stages defined by particular characters, where recapitulation involves heterochrony. Heterochrony represents a gradual alteration in the original phylogenetic sequence due to embryonic adaptation.[11] As well, von Baer early noted that embryos of different species could not be easily distinguished from one another as in adults.

Von Baer's laws governing embryonic development are specific rejections of recapitulation.[6] As a response to Haeckel's theory of recapitulation, von Baer enunciates his most notorious laws of development. Von Baer's laws state that general features of animals appear earlier in the embryo than special features, where less general features stem from the most general, each embryo of a species departs more and more from a predetermined passage through the stages of other animals, and there is never a complete morphological similarity between an embryo and a lower adult.[12] Von Baer's embryo drawings[13][14] display that individual development proceeds from general features of the developing embryo in early stages through differentiation into special features specific to the species, establishing that linear evolution could not occur.[15] Embryological development, in von Baer's mind, is a process of differentiation, "a movement from the more homogeneous and universal to the more heterogeneous and individual."[16]

Von Baer argues that embryos will resemble each other before attaining characteristics differentiating them as part of a specific family, genus or species, but embryos are not the same as the final forms of lower organisms.

Wilhelm His (1831–1904)

[edit]Wilhelm His was one of Haeckel's most authoritative and primary opponents advocating physiological embryology.[17] His Anatomie menschlicher Embryonen (Anatomy of human embryos) employs a series of his most important drawings chronicling developing embryos from the end of the second week through the end of the second month of pregnancy. In 1878, His begins to engage in serious study of the anatomy of human embryos for his drawings. During the 19th century, embryologists often obtained early human embryos from abortions and miscarriages, postmortems of pregnant women and collections in anatomical museums.[18] In order to construct his series of drawings, His collected specimens which he manipulated into a form that he could operate with.

In His' Normentafel, he displays specific individual embryos rather than ideal types.[19] His does not produce norms from aborted specimens, but rather visualizes the embryos in order to make them comparable and specifically subjects his embryo specimens to criticism and comparison with other cases. Ultimately, His' critical work in embryonic development comes with his production of a series of embryo drawings of increasing length and degree of development.[20] His' depiction of embryological development strongly differs from Haeckel's depiction, for His argues that the phylogenetic explanation of ontogenetic events is unnecessary. His argues that all ontogenetic events are the "mechanical" result of differential cell growth.[21] His' embryology is not explained in terms of ancestral history.

The debate between Haeckel and His ultimately becomes fueled by the description of an embryo that Wilhelm Krause propels directly into the ongoing feud between Haeckel and His. Haeckel speculates that the allantois is formed in a similar way in both humans and other mammals. His, on the other hand, accuses Haeckel of altering and playing with the facts. Although Haeckel is proven right about the allantois, the utilization of Krause's embryo as justification turns out to be problematic, for the embryo is that of a bird rather than a human. The underlying debate between Haeckel and His derives from differing viewpoints regarding the similarity or dissimilarity of vertebrate embryos. In response to Haeckel's evolutionary claim that all vertebrates are essentially identical in the first month of embryonic life as proof of common descent, His responds by insisting that a more skilled observer would recognize even sooner that early embryos can be distinguished. His also counteracts Haeckel's sequence of drawings in the Anthropogenie with what he refers to as "exact" drawings, highlighting specific differences. Ultimately, His goes so far as to accuse Haeckel of "faking" his embryo illustrations to make the vertebrate embryos appear more similar than in reality. His also accuses Haeckel of creating early human embryos that he conjured in his imagination rather than obtained through empirical observation. His completes his denunciation of Haeckel by pronouncing that Haeckel had "'relinquished the right to count as an equal in the company of serious researchers.'"[22]

Controversy

[edit]The exactness of Ernst Haeckel's drawings of embryos has caused much controversy among Intelligent Design proponents recently and Haeckel's intellectual opponents in the past. Although the early embryos of different species exhibit similarities, Haeckel apparently exaggerated these similarities in support of his Recapitulation theory, sometimes known as the Biogenetic Law or "Ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny". Furthermore, Haeckel even proposed theoretical life-forms to accommodate certain stages in embryogenesis. A recent review concluded that the "biogenetic law is supported by several recent studies – if applied to single characters only".[23]

Critics in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Karl von Baer and Wilhelm His, did not believe that living embryos reproduce the evolutionary process and produced embryo drawings of their own[24] which emphasized the differences in early embryological development. Late 20th and early 21st century critic Stephen Jay Gould[25] has objected to the continued use of Haeckel's embryo drawings in textbooks.

On the other hand, Michael K. Richardson, Professor of Evolutionary Developmental Zoology, Leiden University, while recognizing that some criticisms of the drawings are legitimate (indeed, it was he and his co-workers who began the modern criticisms in 1998), has supported the drawings as teaching aids,[26] and has said that "on a fundamental level, Haeckel was correct."[27]

Opposition to Haeckel

[edit]Haeckel encountered numerous oppositions to his artistic depictions of embryonic development during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Haeckel's opponents believe that he de-emphasizes the differences between early embryonic stages in order to make the similarities between embryos of different species more pronounced.[28]

Early opponents: Ludwig Rutimeyer, Theodor Bischoff and Rudolf Virchow

[edit]The first suggestion of fakery against Haeckel was made in late 1868 by Ludwig Rutimeyer in the Archiv für Anthropogenie.[28] Rutimeyer was a professor of zoology and comparative anatomy at the University of Basel, who rejected natural selection as simply mechanistic and proposed an anti-materialist view of nature. Rutimeyer claimed that Haeckel "had taken to kinds of liberty with established truth".[29] Rutimeyer claimed that Haeckel presented the same image three consecutive times as the embryo of the dog, the chicken, and the turtle.[30]

Theodor Bischoff (1807–1882), was a strong opponent of Darwinism.[citation needed] As a pioneer in mammalian embryology, he was one of Haeckel's strongest critics.[citation needed] Although Bischoff's 1840 surveys depict how similar the early embryos of man are to other vertebrates, he later demanded that such hasty generalization was inconsistent with his recent findings regarding the dissimilarity between hamster embryos and those of rabbits and dogs.[citation needed] Nevertheless, Bischoff's main argument was in reference to Haeckel's drawings of human embryos, for Haeckel is later accused of miscopying the dog embryo from him.[28] Throughout Haeckel's time, criticism of his embryo drawings was often due in part to his critics' belief in his representations of embryological development as "crude schemata".[31]

Contemporary criticism of Haeckel: Michael Richardson and Stephen Jay Gould

[edit]Michael Richardson and his colleagues in a July 1997 issue of Anatomy and Embryology,[32] demonstrated that Haeckel falsified his drawings in order to exaggerate the similarity of the phylotypic stage. In a March 2000 issue of Natural History, Stephen Jay Gould argued that Haeckel "exaggerated the similarities by idealizations and omissions." As well, Gould argued that Haeckel's drawings are simply inaccurate and falsified.[33] On the other hand, one of those who criticized Haeckel's drawings, Michael Richardson, has argued that "Haeckel's much-criticized drawings are important as phylogenetic hypotheses, teaching aids, and evidence for evolution".[34] But even Richardson admitted in Science Magazine in 1997 that his team's investigation of Haeckel's drawings were showing them to be "one of the most famous fakes in biology."[35]

Some version of Haeckel's drawings can be found in many modern biology textbooks in discussions of the history of embryology, with clarification that these are no longer considered valid.[36]

Haeckel's proponents (past and present)

[edit]Although Charles Darwin accepted Haeckel's support for natural selection, he was tentative in using Haeckel's ideas in his writings; with regard to embryology, Darwin relied far more on von Baer's work. Haeckel's work was published in 1866 and 1874, years after Darwin's "The Origin of Species" (1859).

Despite the numerous oppositions, Haeckel has influenced many disciplines in science in his drive to integrate such disciplines of taxonomy and embryology into the Darwinian framework and to investigate phylogenetic reconstruction through his Biogenetic Law. As well, Haeckel served as a mentor to many important scientists, including Anton Dohrn, Richard and Oscar Hertwig, Wilhelm Roux, and Hans Driesch.[37]

One of Haeckel's earliest proponents was Carl Gegenbaur at the University of Jena (1865–1873), during which both men were absorbing the impact of Darwin's theory. The two quickly sought to integrate their knowledge into an evolutionary program. In determining the relationships between "phylogenetic linkages" and "evolutionary laws of form," both Gegenbaur and Haeckel relied on a method of comparison.[38] As Gegenbaur argued, the task of comparative anatomy lies in explaining the form and organization of the animal body in order to provide evidence for the continuity and evolution of a series of organs in the body. Haeckel then provided a means of pursuing this aim with his biogenetic law, in which he proposed to compare an individual's various stages of development with its ancestral line. Although Haeckel stressed comparative embryology and Gegenbaur promoted the comparison of adult structures, both believed that the two methods could work in conjunction to produce the goal of evolutionary morphology.[39]

The philologist and anthropologist, Friedrich Müller, used Haeckel's concepts as a source for his ethnological research, involving the systematic comparison of the folklore, beliefs and practices of different societies. Müller's work relies specifically on theoretical assumptions that are very similar to Haeckel's and reflects the German practice to maintain strong connections between empirical research and the philosophical framework of science. Language is particularly important, for it establishes a bridge between natural science and philosophy.[40] For Haeckel, language specifically represented the concept that all phenomena of human development relate to the laws of biology.[41] Although Müller did not specifically have an influence in advocating Haeckel's embryo drawings, both shared a common understanding of development from lower to higher forms, for Müller specifically saw humans as the last link in an endless chain of evolutionary development.[42]

Modern acceptance of Haeckel's Biogenetic Law, despite current rejection of Haeckelian views, finds support in the certain degree of parallelism between ontogeny and phylogeny. A. M. Khazen, on the one hand, states that "ontogeny is obliged to repeat the main stages of phylogeny."[43] A. S. Rautian, on the other hand, argues that the reproduction of ancestral patterns of development is a key aspect of certain biological systems. Dr. Rolf Siewing acknowledges the similarity of embryos in different species, along with the laws of von Baer, but does not believe that one should compare embryos with adult stages of development.[43] According to M. S. Fischer, reconsideration of the Biogenetic Law is possible as a result of two fundamental innovations in biology since Haeckel's time: cladistics and developmental genetics.[44]

In defense of Haeckel's embryo drawings, the principal argument is that of "schematisation."[45] Haeckel's drawings were not intended to be technical and scientific depictions, but rather schematic drawings and reconstructions for a specifically lay audience.[45] Therefore, as R. Gursch argues, Haeckel's embryo drawings should be regarded as "reconstructions." Although his drawings are open to criticism, his drawings should not be considered falsifications of any sort. Although modern defense of Haeckel's embryo drawings still considers the inaccuracy of his drawings, charges of fraud are considered unreasonable. As Erland Nordenskiöld argues, charges of fraud against Haeckel are unnecessary. R. Bender ultimately goes so far as to reject His's claims regarding the fabrication of certain stages of development in Haeckel's drawings, arguing that Haeckel's embryo drawings are faithful representations of real stages of embryonic development in comparison to published embryos.[46]

Use of embryo drawings in contemporary biology

[edit]Although Stephen Jay Gould's 1977 book Ontogeny and Phylogeny helps to reassess Haeckelian embryology, it does not address the controversy over Haeckel's embryo drawings. Nevertheless, new interest in evolution in and around 1977 inspired developmental biologists to look more closely at Haeckel's illustrations.[47]

In current biology, fundamental research in developmental biology and evolutionary developmental biology is no longer driven by morphological comparisons between embryos, but more by molecular biology.

See also

[edit]- Medical illustration

- Recapitulation theory

- Ernst Haeckel

- Evolutionary developmental biology

- Embryogenesis

- History of biology

- History of zoology, post-Darwin

- Science education

References

[edit]- ^ Richardson and Keuck, "Haeckel's ABC of evolution and development," p. 516

- ^ Nyhart, Biology Takes Form, pp. 132–133

- ^ Hopwood, "Pictures of Evolution and Charges of Fraud", p. 264

- ^ Richardson and Keuck, "Haeckel's ABC of evolution and development," p. 497

- ^ Nyhart, Biology Takes Form, p. 9

- ^ a b Richardson and Keuck, "Haeckel's ABC of evolution and development," p. 506

- ^ Nyhart, Biology Takes Form, p. 159

- ^ Richardson and Keuck, "Haeckel's ABC of evolution and development," p. 499

- ^ Richardson and Keuck, "Haeckel's ABC of evolution and development," p. 500

- ^ Hopwood, "Pictures of Evolution and Charges of Fraud", p. 270

- ^ Richardson, Michael K. and Gerhard Keuck, "Haeckel's ABC of Evolution and Development," p. 506

- ^ Gould, Ontogeny and Phylogeny, p. 56

- ^ "Histories of development". Making Visible Embryos.

- ^ Erki Tammiksaar; Sabine Brauckmann (2004). "Karl Ernst von Baer's 'Über Entwickelungsgeschichte der Thiere II' and its Unpublished Drawings". History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences. 26 (3/4): 291–308, 471–474. JSTOR 23333718. PMID 16302690.

- ^ Richards, The Meaning of Evolution, pp. 57–59

- ^ Richards, The Meaning of Evolution, pp. 59–60

- ^ Gould, Ontogeny and Phylogeny, p. 189

- ^ Hopwood, "Producing Development", p. 38

- ^ Hopwood, "Producing Development", p. 36

- ^ Hopwood, "Producing Development", p. 50

- ^ Di Gregorio, From Here to Eternity, p. 277

- ^ Hopwood, "Producing Development", p. 61

- ^ Richardson Michael K., Keuck Gerhard (2002). "Haeckel's ABC of evolution and development". Biol. Rev. 77 (4): 495–528. doi:10.1017/s1464793102005948. PMID 12475051. S2CID 23494485.

- ^ "Developmental Similarities: Karl von Baer". University of California Museum of Paleontology. Retrieved 13 March 2012.

- ^ Gould, Stephen Jay. "Abscheulich! (Atrocious!): Haeckel's distortions did not help Darwin". Nat. Hist. 109 (March 2000): 42–49.

- ^ "Haeckel's much-criticized drawings are important as phylogenetic hypotheses, teaching aids, and evidence for evolution. While some criticisms of the drawings are legitimate, others are more tendentious.", M. K. Richardson and G. Keuck, "Haeckel's ABC of evolution and development", Biol. Rev. (2002) 77, 495–528 (quote from abstract)

- ^ Letter to Science, 280, (15 May 1998), 983–984.

- ^ a b c Hopwood, "Pictures of Evolution and Charges of Fraud", p. 282

- ^ Hopwood, "Pictures of Evolution and Charges of Fraud", p. 283

- ^ Hopwood, "Pictures of Evolution and Charges of Fraud", p. 275

- ^ Hopwood, "Pictures of Evolution and Charges of Fraud", p. 273

- ^ Richardson, M.K., Hanken, J., Gooneratne, M.L., Pieau, C., Raynaud. A., Selwood, L. and Wright, G.M. (1997): There is no highly conserved embryonic stage in the vertebrates: implications for current theories of evolution and development. Anatomy and Embryology 196(2): 91–106.

- ^ Stephen Jay Gould (March 2000). "Abscheulich! – Atrocious! – the precursor to the theory of natural selection". Natural History.

- ^ Richardson Michael K., Keuck Gerhard (2002). "Haeckel's ABC of evolution and development". Biol. Rev. 77 (4): 495–528. doi:10.1017/s1464793102005948. PMID 12475051. S2CID 23494485.

- ^ Pennisi, Elizabeth (1997). "Haeckel's Embryos: Fraud Rediscovered". Science. 277 (5331): 1435. doi:10.1126/science.277.5331.1435a. PMID 9304211. S2CID 36959449.

- ^ Futuyma, Douglas, "Evolutionary Biology," pp. 652–653

- ^ Richardson, Michael K. and Gerhard Keuck, "Haeckel's ABC of evolution and development," p. 496

- ^ Nyhart, Lynn K., Biology Takes Form, p. 150

- ^ Nyhart, Lynn K., Biology Takes Form, p. 153

- ^ Di Gregorio, Mario A., From Here to Eternity: Ernst Haeckel and Scientific Faith, p. 253

- ^ Di Gregorio, Mario A., From Here to Eternity: Ernst Haeckel and Scientific Faith, p. 252

- ^ Di Gregorio, Mario A., From Here to Eternity: Ernst Haeckel and Scientific Faith, p. 254

- ^ a b Richardson, Michael K. and Gerhard Keuck, "Haeckel's ABC of Evolution and Development," p. 501

- ^ Richardson, Michael K. and Gerhard Keuck, "Haeckel's ABC of Evolution and Development," p. 502

- ^ a b Richardson, Michael K. and Gerhard Keuck, "Haeckel's ABC of Evolution and Development," p. 519

- ^ Richardson, Michael K. and Gerhard Keuck, "Haeckel's ABC of Evolution and Development," p. 520

- ^ Hopwood, "Pictures of Evolution and Charges of Fraud," p. 298

Further reading

[edit]- Di Gregorio, Mario A. (2005). From Here to Eternity: Ernst Haeckel and Scientific Faith. Göttingen, Germany: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Futuyma, Douglas (1998). Evolutionary Biology (3rd ed.). Sinauer. pp. 652–653.

- Gould, Stephen Jay (1977). Ontogeny and Phylogeny. Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674639409.

- Hopwood, Nick (2006). "Pictures of Evolution and Charges of Fraud: Ernst Haeckel's Embryological Illustrations" (PDF). Isis; an International Review Devoted to the History of Science and Its Cultural Influences. 97 (2). Isis: 260–301. doi:10.1086/504734. PMID 16892945. S2CID 37091078. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 November 2007.

- Hopwood, Nick (2000). "Producing Development: The Anatomy of Human Embryos and the Norms of Wilhelm His". The Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 74 (1): 29–71. doi:10.1353/bhm.2000.0020. PMID 10740908. S2CID 40294481.

- Judson, Horace Freeland (2004). The Great Betrayal: Fraud in Science. Orlando, Florida: Harcourt, Inc. ISBN 978-0-15-100877-3.

- Nordenskiold, Erik (1928). The History of Biology: A Survey. New York, New York: Tudor Publishing Co.

- Nyhart, Lynn K. (1995). Biology Takes Form: Animal Morphology and the German Universities, 1800–1900. Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-61088-7.

- Richards, Robert J. (1992). The Meaning of Evolution: The Morphological Construction and Ideological Reconstruction of Darwin's Theory. Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-71202-4.

- Richardson, Michael K.; Keuck, Gerhard (2002). "Haeckel's ABC of evolution and development". Biological Reviews. 77 (4): 495–528. doi:10.1017/S1464793102005948. PMID 12475051. S2CID 23494485.

- Wells, Jonathan (2000). Icons of Evolution: Science or Myth? Why much of what we teach about evolution is wrong. Washington, DC: Regnery Publishing, Inc. ISBN 978-0-89526-276-9.

- Wells, Jonathan. "Survival of the Fakest". The American Spectator. No. December 2000/January 2001.