History of the Jews in Zimbabwe

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 200 | |

| Languages | |

| English, Hebrew, Yiddish | |

| Religion | |

| Judaism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| South African Jews |

| Part of a series on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

| History of Zimbabwe | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ancient history

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

White settlement pre-1923

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

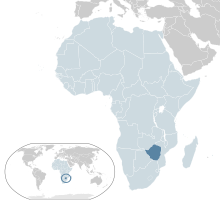

The history of the Jews in Zimbabwe reaches back over one century. Present-day Zimbabwe was formerly known as Southern Rhodesia and later as Rhodesia.

History

[edit]During the 19th century, Ashkenazi Jews from Russian Empire Ukrainian Polish Russia and Belarusian Lithuania settled in Rhodesia after the area had been colonized by the British, and became active in the trading industry. In 1894, the first synagogue was established in a tent in Bulawayo. The second community developed in Salisbury (later renamed Harare) in 1895. A third congregation was established in Gwelo in 1901. By 1900, approximately 300 Jews lived in Rhodesia.

In the 1930s a number of Sephardic Jews arrived in Rhodesia from the Greek island of Rhodes and mainly settled in Salisbury. This was followed by another wave in the 1960s when Jews fled the Belgian Congo . A Sephardic Jewish Community Synagogue was established in Salisbury in the 1950s.[1]

In the late 1930s, German Jews fleeing Nazi persecution settled in the colony. In 1943, the Rhodesian Zionist Council and the Rhodesian Jewish Board of Deputies were established, later being renamed the Central African Zionist Council and Central African Board of Jewish Deputies in 1946.[2] After World War II, Jewish immigrants arrived from South Africa and the United Kingdom. By 1961, the Jewish population peaked at 7,060.[citation needed]

In the first half of the 20th century there was a high level of assimilation by Rhodesian Jews into Rhodesian society, and intermarriage rates were high. Roy Welensky, the second and last Prime Minister of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, was the son of a Lithuanian Jewish father and an Afrikaner mother.[3] By 1957, one out of every seven Jews who married in Rhodesia married a Gentile.[4]

In addition to the Rhodesian Zionist Council and the Rhodesian Jewish Board of Deputies the Jewish Community developed institutions to serve and strengthen the community including two Jewish Day Schools (one in Harare called Sharon School and one in Bulawayo called Carmel School), community centers, Jewish Cemeteries, Zionist youth movements, Jewish owned sports clubs, Savyon Old Age Home in Bulawayo and several women's organisations. A number of Jews from Zionist youth movements emigrated to Israel.[5]

In 1965, the white minority government of Southern Rhodesia, under Prime Minister Ian Smith, unilaterally declared independence as Rhodesia, in response to British demands that the colony be handed over to black majority rule. Rhodesia was then subject to international sanctions, and black nationalist organizations began an insurgency, known as the Rhodesian Bush War, which lasted until 1979, when the Rhodesian government agreed to settle with the black nationalists. By the time the Rhodesian Bush War ended in 1979, most of the country's Jewish population had emigrated,[citation needed] along with many other whites.

Some Jews chose to stay behind when the country was transferred to black majority rule and renamed Zimbabwe in 1980. However, emigration continued, and by 1987, only 1,200 Jews out of an original population of some 7,000 remained. Most Rhodesian Jews emigrated to Israel or South Africa, seeking better economic conditions and Jewish marriage prospects. Until the late 1990s, rabbis resided in Harare and Bulawayo, but left as the economy and community began to decline. Today there is no resident Rabbi.[citation needed]

In 1992, President Robert Mugabe caused upset to the Jewish community in Zimbabwe when he remarked that "[white] commercial farmers are hard-hearted people, you would think they were Jews".[6]

In 2002, after the Jewish community's survival was threatened by a food shortage and poverty in the country, the mayor of Ashkelon, a city in southern Israel, invited Zimbabwean Jews to immigrate to Israel and offered assistance in settling in Ashkelon. Several Zimbabwean Jews accepted his offer.[citation needed]

In 2003 the Bulawayo Synagogue burned down and the small community did not restore the building. Prayers are generally held at the Sinai Hall or Savyon Lodge in Bulawayo. In Harare the Sephardic Community has its own synagogue, and the Ashkenazi Community has a separate synagogue. Today because of small numbers of congregants the prayers alternate between the two synagogues.[5]

Today, about 200 Jews live in Zimbabwe, chiefly in Harare and Bulawayo. There are no Jews remaining in Kwekwe, Gweru, and Kadoma. Two-thirds of Zimbabwean Jews are over 65 years of age. The last bar mitzvah took place in 2006.[7]

| Year | Jewish population of Zimbabwe |

|---|---|

| 1894 | 20[8] |

| 1900 | 300 |

| 1921 | 1,289[8] |

| 1936 | 2,219[9] |

| 1947 | 2,021[10] |

| 1951 | 4,760 [9] |

| 1961 | 7,061[8] |

| 1970s | 7,500[11] |

| 1980 | 1,550[12] |

| 1987 | 1,200 |

| 1989 | 1,168[13] |

| 2001 | 800 |

| 2004 | 400 |

| 2006 | 99[14] |

| 2014 | 120[7] |

| 2019 | 200[15] |

Lemba people

[edit]The Lemba people speak the Bantu languages spoken by their geographic neighbours and resemble them physically, but they have some religious practices and beliefs similar to those in Judaism and Islam,[citation needed] which they claim were transmitted by oral tradition.{cn}} They have a tradition of ancient Jewish or South Arabian descent through their male line.{cn}}[16] Genetic Y-DNA analyses in the 2000s have established a partially Middle-Eastern origin for a portion of the male Lemba population.[17][18] More recent research argues that DNA studies do not support claims for a specifically Jewish genetic heritage.[19][20]

See also

[edit]- History of the Jews in Malawi

- History of the Jews in Mozambique

- History of the Jews in South Africa

- History of the Jews in Southern Africa

- History of the Jews in Zambia

- Israel–Zimbabwe relations

References

[edit]- ^ "Sephardi Hebrew Congregation of Zimbabwe". Archived from the original on 2021-10-29. Retrieved 2014-11-25.

- ^ Jewish Communities of the World, Anthony Lerman, Springer, 1989, page 195

- ^ Sir Roy Welensky, 84, Premier of African Federation, Is Dead, New York Times, December 7, 1991

- ^ Intermarriage Among Jews in Rhodesia Viewed As "Alarming", Jewish Telegraphic Agency, October 16, 1957

- ^ a b Zimbabwe Jewish Community

- ^ Jews upset by Mugabe comment, The Independent, 20 July 1992

- ^ a b Berg, Elaine (March 2014). "Our Month With the Lemba, Zimbabwe's Jewish Tribe". The Jewish Daily Forward. The Forward Association. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- ^ a b c "Zimbabwe Virtual Jewish History Tour". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 2023-06-24.

- ^ a b "Zimbabwe". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 2024-02-18.

- ^ Eastman Irvine, E., ed. (1947). The World Almanac and Book of Facts for 1947. p. 219.

- ^ "Travelling rabbi battles killer bees in Zimbabwe". www.thejc.com. Retrieved 2022-09-02.

- ^ DELLA PERGOLA, SERGIO (1982). World Jewish Population. p. 278.

- ^ Lerman, Anthony (1989-06-18). Jewish Communities of the World. Springer. p. 197. ISBN 978-1-349-10532-8.

- ^ "The Jewish population of Victoria" (PDF).

- ^ "2019 World Jewish Population" (PDF).

- ^ van Warmelo, N.J. (1966). "Zur Sprache und Herkunft der Lemba". Hamburger Beiträge zur Afrika-Kunde. 5. Deutsches Institut für Afrika-Forschung: 273, 278, 281–282.

- ^ Spurdle, AB; Jenkins, T (November 1996), "The origins of the Lemba "Black Jews" of southern Africa: evidence from p12F2 and other Y-chromosome markers.", Am. J. Hum. Genet., 59 (5): 1126–33, PMC 1914832, PMID 8900243

- ^ Kleiman, Yaakov (2004). DNA and Tradition – Hc: The Genetic Link to the Ancient Hebrews. Devora Publishing. p. 81. ISBN 1-930143-89-3.

- ^ Tofanelli Sergio, Taglioli Luca, Bertoncini Stefania, Francalacci Paolo, Klyosov Anatole, Pagani Luca, "Mitochondrial and Y chromosome haplotype motifs as diagnostic markers of Jewish ancestry: a reconsideration", Frontiers in Genetics Volume 5, 2014, [1] DOI=10.3389/fgene.2014.00384

- ^ Himla Soodyall; Jennifer G. R Kromberg (29 October 2015). "Human Genetics and Genomics and Sociocultural Beliefs and Practices in South Africa". In Kumar, Dhavendra; Chadwick, Ruth (eds.). Genomics and Society: Ethical, Legal, Cultural and Socioeconomic Implications. Academic Press/Elsevier. p. 316. ISBN 978-0-12-420195-8.